Designing A Practical Political Risk Framework

Key takeaways:

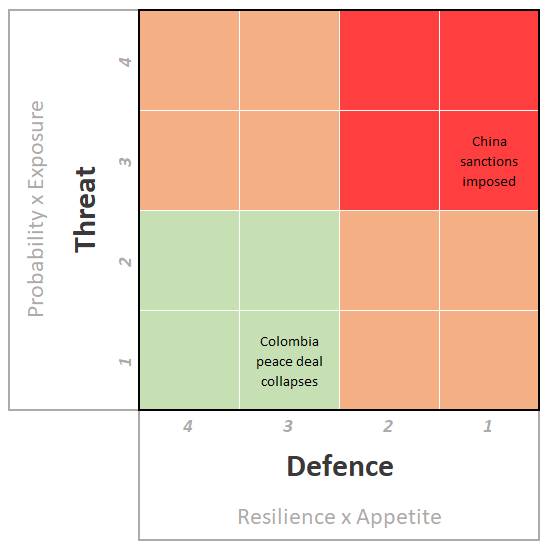

- Political risks can be quantified and represented within a single matrix

- Threats to the business must be mapped against its willingness and ability to absorb risks

- An effective risk matrix helps senior managers reallocate resources

- Executives at national or functional level can identify their own risk and response picture

Previous articles in our geopolitical risk series have introduced the elements needed to identify, quantify and prioritise the risks that a company faces; assess a company’s appetite for a given risk in a given circumstance; and help executives throughout the company to prepare for the worst.

Drawing these variables into a simple framework provides decision makers with an overall view of where the company’s geopolitical risks lie thereby helping them allocate resources, assign responsibilities, and ultimately seize good business opportunities. An effective framework can also encourage collaboration between departments that face related risks and require a coordinated response.

Importantly, a risk framework must be tailored to the priorities and structure of each company. The first step to achieve this is to separate the variables that represent the threat level to the business from those that show its capacity or willingness to absorb it. In the former, we count the probability of the risk event occurring and the company’s exposure to it. The threat level is a simple product of these two measures. For defence, we combine the company’s resilience and its appetite for risk. Both calculations can be represented as an indicator on a scale of one to four, though individual companies can refine the scale of measurement if necessary.

Matrix reloaded

Risks can then be plotted in a matrix, colour coded to show at a glance the priorities (see chart below). So a risk with a low threat score and a high defence score would sit in the green quadrant, indicating low priority. But a high threat with a low defence score would sit in the red, high-priority quadrant. Risks with either high threat level and high defence level, or low threat level and low defence level, would sit in orange moderate-priority quadrants.

Source: FT|IE Corporate Learning Alliance

Consider some real-world examples. A Brazilian drinks manufacturer with markets around Latin America might classify the prospect of a collapse in the peace deal between Colombia’s government and FARC insurgency as a risk. The peace deal looks sound, so the probability of this happening is low, and the company might judge its Colombia exposure to be modest in any case. This would equate to a low threat score. At the same time, since the peace deal is recent, the company’s Colombia operations may already be optimised for an insecure situation, so resilience is high. Maintaining a physical presence in the country may be an important element in the company’s appeal to the local market, so it may be willing to accept a higher level of risk (its risk appetite) than otherwise. With both strong resilience and appetite, the defence score for this risk is high. These scores—low threat and high defence—would place the risk firmly in the green quadrant, and resources would be prioritised accordingly. For example, it may be that it that any risk can be dealt with at local level.

“A high threat with a low defence score would sit in the red, high-priority quadrant; companies will need back-up plans and probably senior leadership involvement.”

Meanwhile, a US consumer goods manufacturer might view China’s market quite differently given the prospects of higher tariffs in the wake of the country’s worsening relations with the Trump administration. If the company already has a major operation in China this implies a high risk exposure, especially if leaving the market would damage its global growth. If the company also finds that its local connections turn out not to be as reliable as previously thought, the company may have little resilience against business disruption there. At the same time, if the company’s name and reputation in markets elsewhere are on the line, it may have little appetite for dealing with new problems in China. With a high threat score and a low defence score, this risk would sit in the high-priority red quadrant of the company’s risk register. Companies will need back-up plans if things go wrong, and the global leadership may need to be involved.

The matrix can be repeated at departmental level too, where the variables may differ from the general company level. For instance, a local subsidiary may see a mix of threats to its operations from a transport strike against public sector reforms. For operations and procurement, the threat may be severe; for finance and marketing it may be modest. Separate risk matrices for each of these departments will reflect the degree of threat they face and help to determine how much attention should be paid to the underlying risk.

Each company will go through its full register of political risks, assign them threat and defence scores, and locate them on the matrix. Fully populated and regularly updated – as new threats emerge and departments enhance their resilience or reduce exposure – the matrix provides senior management with an instant, up-to-date view of the number and intensity of major geopolitical risks worldwide. A bias towards amber and green may free up resources for other uses. A preponderance of risks in the red quadrant will alert the management to the need for more resources and action should the worst happen.

A version of this article was first published in CEO Magazine.